Sex, brain cells and memory loss

The case of the 54-year-old woman who admitted herself to the Georgetown University Medical School emergency department complaining of severe memory loss triggered by sex was widely reported last month: “Mind-blowing sex can wipe memory clean,” ran the Live Science headline; “For one woman, sex was mind-blowing and, literally, totally forgettable, all at the same time,” said ABC News; “Over-exertion between the sheets can wipe your memory,” warned the Daily Mail.

The woman had suffered an episode of a condition called transient global amnesia (TGA), a ‘pure’ memory syndrome characterized by abrupt, severe memory loss in the absence of other neurological deficits. Although extremely rare and poorly understood, TGA is helping researchers to gain a better understanding of the neuroanatomical basis of memory. The symptoms also bear a close resemblance to those observed in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s Disease.

This mysterious condition was first described by French physicians in 1956. Since then, there have only been several hundred documented cases. The causes are still unknown, but recent evidence suggests it might be due to congestion in the veins that drain blood from the brain. Many of the cases appear to be precipitated by strenuous physical activity, but it can also be triggered by psychologically and emotionally stressful events as well as physiologically stressful ones, such as taking a hot or cold shower. Most often, the precipitating event occurs immediately before the onset of amnesia; more rarely, it can precede the memory loss by days, weeks or even months.

This latest case of sex-induced TGA – there have been others – was reported in the Journal of Emergency Medicine in September. The woman told doctors that her memory loss had coincided with sexual climax about an hour earlier. Her husband corroborated this, adding that she was unable to recall events that had occurred within the preceding 24 hours and could not incorporate new memories. These symptoms lasted about 20 minutes and had almost completely disappeared by the time the couple had arrived at hospital. Throughout the episode, the woman had remained fully cognizant – she was fully conscious, alert and conversant.

The case seems to be typical of the condition. The vast majority of cases occur in middle-aged and elderly people, most of whom have no history of other neurological events, such as migraine or head trauma. In the small number of younger patients, however, a history of headaches could be an important risk factor. In all cases, memory gradually recovers 2-10 hours after the precipitating event, leaving only a gap for the events that occurred during the episode and often for events that occurred in the hours preceding it.

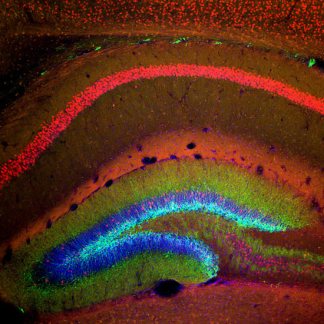

Thorsten Bartsch of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, Germany and his colleagues have shown that TGA is associated with localized damage to the hippocampus, a part of the brain which is well known to play a critical role in the formation and recollection of autobiographical memories, or memories for life events.

In 2006, they published the results of a neuroimaging study involving 41 TGA patients. Twenty-nine of these patients had small lesions that were restricted to the CA1 region of the hippocampus (seen on the right in the image at the top). The damage could be detected within 6 hours of the onset of symptoms, but was no longer visible in brain scans performed on the patients 4-6 months later.

Bartsch and his colleagues confirm these findings in another study published last month. This time, they scanned the brains of 16 more TGA patients and found exactly the same transient lesions in 14 of them. All the patients had experienced severe memory loss for life events that extended back 30 years or more. In all cases, the amnesia was restricted to autobiographical memory and memory function was restored within 24 hours.

“Imaging these lesions is not easy as they are so small, transient and focal,” says Bartsch, “but we have developed sensitive measures. Timing is crucial as the window of amnesia only lasts about 12 hours. After that, the patient quickly recovers. The lesion is best seen after 24-72 hours, but is gone after 5-6 days. Our guess is that the quick recovery is largely due to a quick reorganisation and compensation within the hippocampal network.”

Interestingly, those patients with damage located further towards the front end of the CA1 region had greater impairment for the most remote autobiographical memories. This lends some support to earlier work which suggests that recollection of distant memories involves activation along the entire front-to-back extent of the hippocampus and that retrieval of the most distant memories is more dependent on activity at the front end.

Memory is a form of mental time travel, enabling us to “traverse times and spaces far remote.” The reconstructive nature of memory also enables us to travel forward in time, by piecing together fragments of events we have already experienced to imagine those that have not yet occurred. And another very recent study by a team of French researchers shows that TGA patients not only have dificulty recalling their past, but also have difficulty imagining the future.

Studying this mysterious condition may help researchers to understand the cellular events underlying the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The earliest stages of Alzeimer’s involve degeneration of the CA1 region of the hippocampus, and this is accompanied by memory deficits that are very similar to those seen in TGA. “It is very interesting that the same neurons are affected very early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Bartsch. “TGA is somehow a model for the disease. It sheds some light on the deficit in Alzheimer’s and the putative target for a cure.”

-Courtesy http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/neurophilosophy/2011/nov/04/1#