Theory of Relativity – A Brief History

The Theory of Relativity, proposed by the Jewish physicist Albert Einstein (1879-1955) in the early part of the 20th century, is one of the most significant scientific advances of our time. Although the concept of relativity was not introduced by Einstein, his major contribution was the recognition that the speed of light in a vacuum is constant and an absolute physical boundary for motion. This does not have a major impact on a person’s day-to-day life since we travel at speeds much slower than light speed. For objects travelling near light speed, however, the theory of relativity states that objects will move slower and shorten in length from the point of view of an observer on Earth. Einstein also derived the famous equation, E = mc2, which reveals the equivalence of mass and energy.

When Einstein applied his theory to gravitational fields, he derived the “curved space-time continuum” which depicts the dimensions of space and time as a two-dimensional surface where massive objects create valleys and dips in the surface. This aspect of relativity explained the phenomena of light bending around the sun, predicted black holes as well as the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation (CMB) — a discovery rendering fundamental anomalies in the classic Steady-State hypothesis. For his work on relativity, the photoelectric effect and blackbody radiation, Einstein received the Nobel Prize in 1921.

Theory of Relativity – The Basics

Physicists usually dichotomize the Theory of Relativity into two parts.

- The first is the Special Theory of Relativity, which essentially deals with the question of whether rest and motion are relative or absolute, and with the consequences of Einstein’s conjecture that they are relative.

- The second is the General Theory of Relativity, which primarily applies to particles as they accelerate, particularly due to gravitation, and acts as a radical revision of Newton’s theory, predicting important new results for fast-moving and/or very massive bodies. The General Theory of Relativity correctly reproduces all validated predictions of Newton’s theory, but expands on our understanding of some of the key principles. Newtonian physics had previously hypothesised that gravity operated through empty space, but the theory lacked explanatory power as far as how the distance and mass of a given object could be transmitted through space. General relativity irons out this paradox, for it shows that objects continue to move in a straight line in space-time, but we observe the motion as acceleration because of the curved nature of space-time.

Einstein’s theories of both special and general relativity have been confirmed to be accurate to a very high degree over recent years, and the data has been shown to corroborate many key predictions; the most famous being the solar eclipse of 1919 bearing testimony that the light of stars is indeed deflected by the sun as the light passes near the sun on its way to earth. The total solar eclipse allowed astronomers to — for the first time — analyse starlight near the edge of the sun, which had been previously inaccessible to observers due to the intense brightness of the sun. It also predicted the rate at which two neutron stars orbiting one another will move toward each other. When this phenomenon was first documented, general relativity proved itself accurate to better than a trillionth of a percent precision, thus making it one of the best confirmed principles in all of physics.

Applying the principle of general relativity to our cosmos reveals that it is not static. Edwin Hubble (1889-1953) demonstrated in 1928 that the Universe is expanding, showing beyond reasonable doubt that the Universe sprang into being a finite time ago. The most common contemporary interpretation of this expansion is that this began to exist from the moment of the Big Bang some 13.7 billion years ago. However this is not the only plausible cosmological model which exists in academia, and many creation physicists such as Russell Humphreys and John Hartnett have devised models operating with a biblical framework, which — to date — have withstood the test of criticism from the most vehement of opponents.

Theory of Relativity – A Testament to Creation

Using the observed cosmic expansion conjunctively with the general theory of relativity, we can infer from the data that the further back into time one looks, the universe ought to diminish in size accordingly. However, this cannot be extrapolated indefinitely. The universe’s expansion helps us to appreciate the direction in which time flows. This is referred to as the Cosmological arrow of time, and implies that the future is — by definition — the direction towards which the universe increases in size. The expansion of the universe also gives rise to the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the overall entropy (or disorder) in the Universe can only increase with time because the amount of energy available for work deteriorates with time. If the universe was eternal, therefore, the amount of usable energy available for work would have already been exhausted. Hence it follows that at one point the entropy value was at absolute 0 (most ordered state at the moment of creation) and the entropy has been increasing ever since — that is, the universe at one point was fully “wound up” and has been winding down ever since. This has profound theological implications, for it shows that time itself is necessarily finite. If the universe were eternal, the thermal energy in the universe would have been evenly distributed throughout the cosmos, leaving each region of the cosmos at uniform temperature (at very close to absolute 0), rendering no further work possible.

The General Theory of Relativity demonstrates that time is linked, or related, to matter and space, and thus the dimensions of time, space, and matter constitute what we would call a continuum. They must come into being at precisely the same instant. Time itself cannot exist in the absence of matter and space. From this, we can infer that the uncaused first cause must exist outside of the four dimensions of space and time, and possess eternal, personal, and intelligent qualities in order to possess the capabilities of intentionally space, matter — and indeed even time itself — into being.

Moreover, the very physical nature of time and space also suggest a Creator, for infinity and eternity must necessarily exist from a logical perspective. The existence of time implies eternity (as time has a beginning and an end), and the existence of space implies infinity. The very concepts of infinity and eternity infer a Creator because they find their very state of being in God, who transcends both and simply is.

The case of the 54-year-old woman who admitted herself to the Georgetown University Medical School emergency department complaining of severe memory loss triggered by sex was widely reported last month: “Mind-blowing sex can wipe memory clean,” ran the Live Science headline; “For one woman, sex was mind-blowing and, literally, totally forgettable, all at the same time,” said ABC News; “Over-exertion between the sheets can wipe your memory,” warned the Daily Mail.

The woman had suffered an episode of a condition called transient global amnesia (TGA), a ‘pure’ memory syndrome characterized by abrupt, severe memory loss in the absence of other neurological deficits. Although extremely rare and poorly understood, TGA is helping researchers to gain a better understanding of the neuroanatomical basis of memory. The symptoms also bear a close resemblance to those observed in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s Disease.

This mysterious condition was first described by French physicians in 1956. Since then, there have only been several hundred documented cases. The causes are still unknown, but recent evidence suggests it might be due to congestion in the veins that drain blood from the brain. Many of the cases appear to be precipitated by strenuous physical activity, but it can also be triggered by psychologically and emotionally stressful events as well as physiologically stressful ones, such as taking a hot or cold shower. Most often, the precipitating event occurs immediately before the onset of amnesia; more rarely, it can precede the memory loss by days, weeks or even months.

This latest case of sex-induced TGA – there have been others – was reported in the Journal of Emergency Medicine in September. The woman told doctors that her memory loss had coincided with sexual climax about an hour earlier. Her husband corroborated this, adding that she was unable to recall events that had occurred within the preceding 24 hours and could not incorporate new memories. These symptoms lasted about 20 minutes and had almost completely disappeared by the time the couple had arrived at hospital. Throughout the episode, the woman had remained fully cognizant – she was fully conscious, alert and conversant.

The case seems to be typical of the condition. The vast majority of cases occur in middle-aged and elderly people, most of whom have no history of other neurological events, such as migraine or head trauma. In the small number of younger patients, however, a history of headaches could be an important risk factor. In all cases, memory gradually recovers 2-10 hours after the precipitating event, leaving only a gap for the events that occurred during the episode and often for events that occurred in the hours preceding it.

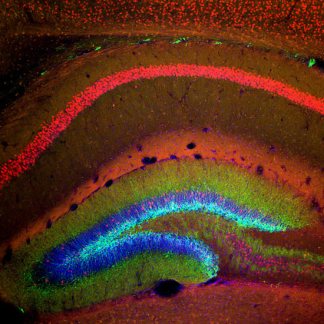

Thorsten Bartsch of University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein in Kiel, Germany and his colleagues have shown that TGA is associated with localized damage to the hippocampus, a part of the brain which is well known to play a critical role in the formation and recollection of autobiographical memories, or memories for life events.

In 2006, they published the results of a neuroimaging study involving 41 TGA patients. Twenty-nine of these patients had small lesions that were restricted to the CA1 region of the hippocampus (seen on the right in the image at the top). The damage could be detected within 6 hours of the onset of symptoms, but was no longer visible in brain scans performed on the patients 4-6 months later.

Bartsch and his colleagues confirm these findings in another study published last month. This time, they scanned the brains of 16 more TGA patients and found exactly the same transient lesions in 14 of them. All the patients had experienced severe memory loss for life events that extended back 30 years or more. In all cases, the amnesia was restricted to autobiographical memory and memory function was restored within 24 hours.

“Imaging these lesions is not easy as they are so small, transient and focal,” says Bartsch, “but we have developed sensitive measures. Timing is crucial as the window of amnesia only lasts about 12 hours. After that, the patient quickly recovers. The lesion is best seen after 24-72 hours, but is gone after 5-6 days. Our guess is that the quick recovery is largely due to a quick reorganisation and compensation within the hippocampal network.”

Interestingly, those patients with damage located further towards the front end of the CA1 region had greater impairment for the most remote autobiographical memories. This lends some support to earlier work which suggests that recollection of distant memories involves activation along the entire front-to-back extent of the hippocampus and that retrieval of the most distant memories is more dependent on activity at the front end.

Memory is a form of mental time travel, enabling us to “traverse times and spaces far remote.” The reconstructive nature of memory also enables us to travel forward in time, by piecing together fragments of events we have already experienced to imagine those that have not yet occurred. And another very recent study by a team of French researchers shows that TGA patients not only have dificulty recalling their past, but also have difficulty imagining the future.

Studying this mysterious condition may help researchers to understand the cellular events underlying the development of Alzheimer’s disease. The earliest stages of Alzeimer’s involve degeneration of the CA1 region of the hippocampus, and this is accompanied by memory deficits that are very similar to those seen in TGA. “It is very interesting that the same neurons are affected very early in the course of Alzheimer’s disease,” says Bartsch. “TGA is somehow a model for the disease. It sheds some light on the deficit in Alzheimer’s and the putative target for a cure.”

-Courtesy http://www.guardian.co.uk/science/neurophilosophy/2011/nov/04/1#

“I think it is very important to find out not how to start, but why you want to do social work at all. Why do you want to do social work ? Is it because you see misery in the world–starvation, disease, exploitation, the brutal indifference of great wealth side by side with appalling poverty, the enmity between man and man ? Is that the reason ?Do you want to do social work because in your heart there is love and therefore you are not concerned with your own fulfillment ? Or is social work a means of escape from yourself ? Do you understand ? You see, for example, all the ugliness involved in orthodox marriage, so you say, “I shall never get married,” and you throw yourself into social work instead; or perhaps your parents have urged you into it, or you have an ideal. If it is a means of escape, or if you are merely pursuing an ideal established by society , by a leader or a priest, or by yourself, then any social work you may do will only create further misery. But if you have love in your heart, if you are seeking truth and are therefore a truly religious person, if you are no longer ambitious, no longer pursuing success, and your virtue is not leading to respectability–then your very life will help to bring about a total transformation of society.

I think it is very important to understand this. When we are young, as most of you are, we want to do something, and social work is in the air; books tell about it, the newspapers do propaganda for it, there are schools to train social workers, and so on. But you see, without self-knowledge, without understanding yourself and your relationships, any social work you do will turn to ashes in your mouth.

It is the happy man, not the idealist or the miserable escapee, who is revolutionary; and the happy man is not he who has many possessions. The happy man is the truly religious man, and his very living is social work. But if you become merely one of the innumerable social workers, your heart will be empty. You may give away your money, or persuade other people to contribute theirs, and you may bring about marvellous reforms; but as long as your heart is empty and your mind full of theories, your life will be dull, weary, without joy. So, first understand yourself, and out of that self-knowledge will come action of the right kind”.